Artikelen

Written by Jane Waldron Grutz and illustrated by Norman MacDonald

![]()

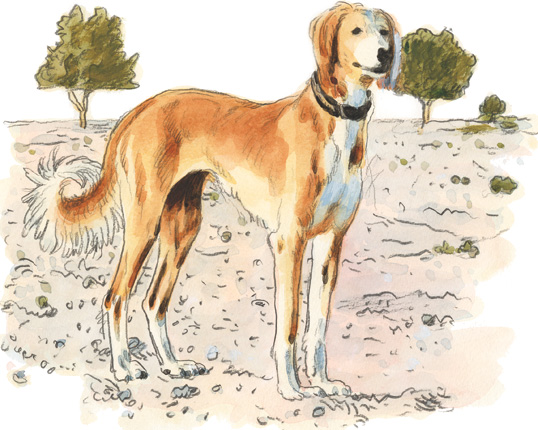

here can be little doubt that Saudi Arabia’s King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz knew a good saluki when he saw one. He had learned the worth of these elegant gazehounds as a boy, when he and his father, ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud, lived with the Al Murrah tribe on the fringes of the Rub’ al-Khali, or Empty Quarter.

here can be little doubt that Saudi Arabia’s King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz knew a good saluki when he saw one. He had learned the worth of these elegant gazehounds as a boy, when he and his father, ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud, lived with the Al Murrah tribe on the fringes of the Rub’ al-Khali, or Empty Quarter.

Exiled from his family’s historical homeland near Riyadh by the rival House of Rashid, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz quickly learned the ways of a tribe renowned for its near-legendary tracking abilities, for its fine black milking camels and, not least, for its swift-running red salukis—the graceful lop-eared hounds that could skim across the desert sands and bring down the fleet gazelle or the nimble desert hare.

To the Al Murrah, and indeed to all Bedouins, the saluki had nothing in common with the kalb, the rough watchdog that guarded their tents. Like the ancient Egyptians before them, the Bedouin honored the saluki as al-hurr, “the noble one,” and poets called it “the prince of swiftness.”

lmost every Al Murrah family had one or two salukis, for without them there would be no small game to eat. The Bedouin depended on his camels for milk and transportation, and it was only on a great occasion, such as the appearance of an honored guest, that he would slaughter so valuable an animal. If it were not for his saluki, the chances of an occasional hare for the family cook-pot would be slim.

lmost every Al Murrah family had one or two salukis, for without them there would be no small game to eat. The Bedouin depended on his camels for milk and transportation, and it was only on a great occasion, such as the appearance of an honored guest, that he would slaughter so valuable an animal. If it were not for his saluki, the chances of an occasional hare for the family cook-pot would be slim.

The treatment accorded this much-favored hound reflected its importance to the family’s welfare. During the heat of the day, the saluki could be found in the shade of the women’s quarters, curled up in a quiet corner or being made much of by the children.

It was in the cool hours of the early morning that the saluki proved its mettle. This was when the children took it out to course the desert hare, scarce during the long, hot summer but reasonably abundant in the early days of spring.

In later years, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz often told stories of his years with the Al Murrah. No one remembers whether he ever mentioned a favorite saluki, but it is known that, by the 1940’s, King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz owned some of the finest salukis in the land.

|

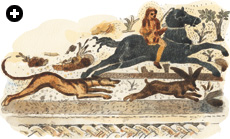

Decorating a gold fly whisk from the tomb of Tutankhamun, a hunting scene includes a dog that resembles a modern saluki. |

The king’s salukis were highly trained hunting dogs that usually accompanied him to the desert for his annual spring hunt, a time when he and his entourage would spend several weeks living as their forefathers had done.

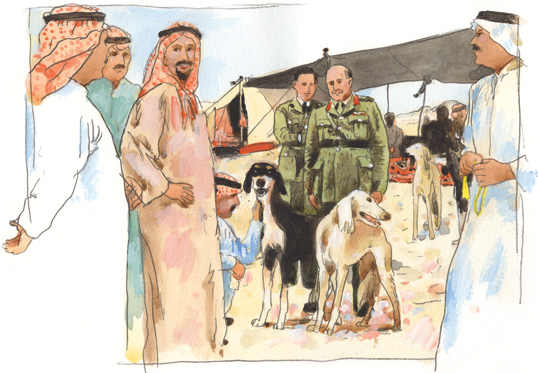

These extended desert forays were important social occasions and, as often as not, distinguished guests would be invited to spend a day or two with the royal party. It was on such an occasion in the early 1940’s that British Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson and his aide Colonel Chapman-Walker were among those in attendance.

It turned out to be a good day’s hunt, with one lively, crop-eared hound in particular showing unusual hunting skills. The guests were delighted with the dog’s performance and applauded him when he appeared. Among the most enthusiastic was Colonel Chapman-Walker, who remarked casually to the king that, of all the hounds he had seen that day, he liked the black-and-tan one best.

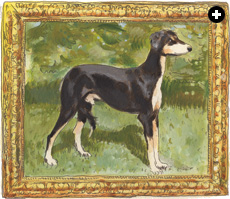

With characteristic Arab generosity, King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz insisted on giving the saluki to the field marshal as a gift of honor, together with a suitable female. The saluki was named Abdul Farouk I and the consort Lady Yeled Sarona Ramullah. The presentation ceremony involved all the pomp appropriate to such an occasion.

The field marshal took Abdul Farouk I and Lady Yeled with him on wartime assignments to Cairo, Algiers, Naples and finally Washington, D.C., where he headed the British Joint Staff Mission. It was when Wilson was about to return to England that a difficulty arose: British regulations called for a six-month quarantine for animals coming from abroad, a hardship so severe that the field marshal decided that, rather than take his beloved dogs with him, he would give them to Esther Bliss Knapp, who was thought to know more about salukis than almost anyone.

For many years, Esther Knapp had served as president of the Saluki Club of America, and she was well known for her monthly column in the American Kennel Club Gazette. As a breeder, her goal at Pine Paddocks kennels in Ohio was not to alter the saluki, but to preserve a breed of dog so perfectly adapted that it had remained unchanged for more than 6000 years. She especially admired salukis with the aristocratic bearing she called “the look of eagles”—and in Abdul Farouk I and Lady Yeled she found two such dogs.

In later years, Knapp became fond of saying, romantically, that Abdul Farouk arrived on a magic carpet. With his elegant head carriage and far-seeing “oriental” eyes—traits that later became characteristic of the Pine Paddocks saluki line—he did seem to create a sort of magic around him. In 1946, he was named the first crop-eared saluki champion in the US, and in 1949 Lady Yeled was named the first US smooth-coated champion bitch.

|

| With characteristic Arab generosity, King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz insisted on giving Abdul Farouk I to the field marshal as a gift of honor, together with a suitable female, Lady Yeled Sarona Ramullah. |

But it was Abdul Farouk’s great-grandson Ahbou Farouk who became one of the greatest saluki show dogs of all time. To Knapp, Ahbou Farouk’s aristocratic bearing seemed to embody the very essence of the breed. Show judges often agreed, and during a career that spanned the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, he won 12 all-breed best-in-show awards, 38 group firsts and many other prizes. He was the first saluki ever to be named to the US list of top 10 hounds and, in the eyes of at least one reviewer, he was number one on that list.

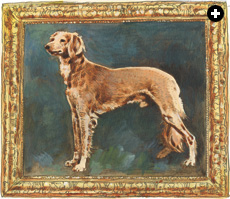

![]() ing ‘Abd al-‘Aziz also made a second canine gift to the West. Sabbah the Windswift never equaled the show-ring success of either Ahbou Farouk or Abdul Farouk I. Indeed, thanks to a broken leg that mended badly, Sabbah never even entered a show ring. But his progeny did, and over a 20-year period, no fewer than 29 out of 64 English champions carried Sabbah’s blood, in addition to many other American, Scandinavian and other champion salukis.

ing ‘Abd al-‘Aziz also made a second canine gift to the West. Sabbah the Windswift never equaled the show-ring success of either Ahbou Farouk or Abdul Farouk I. Indeed, thanks to a broken leg that mended badly, Sabbah never even entered a show ring. But his progeny did, and over a 20-year period, no fewer than 29 out of 64 English champions carried Sabbah’s blood, in addition to many other American, Scandinavian and other champion salukis.

Sabbah had been bred by Amir Muhammad Al Sa‘ud, a nephew of King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and a well-known saluki fancier who had given Sabbah to the king. Although a little stockier than some salukis, Sabbah was nevertheless a handsome fellow with a happy temperament, as the consistently high carriage of his feathery tail attested.

Sabbah had been bred by Amir Muhammad Al Sa‘ud, a nephew of King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and a well-known saluki fancier who had given Sabbah to the king. Although a little stockier than some salukis, Sabbah was nevertheless a handsome fellow with a happy temperament, as the consistently high carriage of his feathery tail attested.

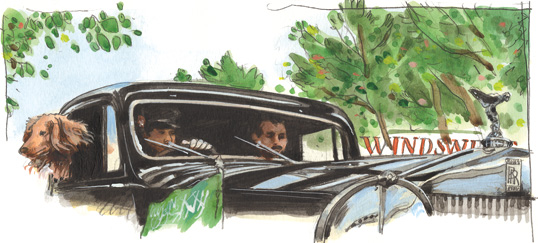

In 1950, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz in turn presented Sabbah as a gift to his ambassador in London, Shaykh Hafiz Wahba. Had the ambassador been living in Saudi Arabia, he would no doubt have been delighted with so fine a gift, but the embassy in London proved to be no place for a lively hunting hound. Indeed, it was when trying to jump the fence of the embassy grounds that Sabbah injured his leg. The inevitable result was a brief but highly persuasive phone call to another woman who knew all about salukis and valued them accordingly.

Years later, Vera Watkins remembered the elegant embassy car that came down the muddy lane leading to her Windswift Kennels. The ambassador sat with his chauffeur in the front seat, she noted, leaving the entire back seat to his regal saluki. And as was fitting, it was the ambassador himself who presented Sabbah to Watkins “with much ceremony.”

|

| Shaykh Wahba’s embassy in London proved no place for a lively hunting hound. |

Sabbah was all Watkins had hoped for—and more than she had expected. In every respect he seemed to represent the best Arabia had to offer and, as the foundation dog of her saluki line, he passed these characteristics on to his offspring. The result was the famous Windswift type saluki, which Watkins described as “smaller than some because of their close desert breeding… but with tremendous personality, beautiful intelligent heads… and superb speed.”

Compact in body—he was only 64 centimeters (25") at the shoulder—Sabbah was full of high spirits and an engaging good will that made everyone fall in love with him—particularly Watkins, who never failed to comment that Sabbah was “full of brains.”

![]() ven today, some 60 years later, Abdul Farouk I and Sabbah the Windswift are revered among saluki fanciers for their elegant conformation, for their grace of movement and, above all, for their intelligence, which enlivened the noble art of hunting.

ven today, some 60 years later, Abdul Farouk I and Sabbah the Windswift are revered among saluki fanciers for their elegant conformation, for their grace of movement and, above all, for their intelligence, which enlivened the noble art of hunting.

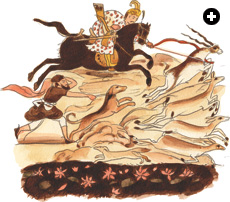

For beautiful as the saluki is, it is first and foremost a hunting hound, and it is that prowess that has enabled the breed to thrive for millennia. No one knows exactly when the saluki originated, though it is generally agreed that the saluki-type hound may have been among the first dogs to be intentionally bred for certain characteristics.

Included in the evidence for this early relationship between humans and dogs are stamp seals dating to between 4000 and 3700 BC from Tepe Gawra in Mesopotamia. On them, the hunting hounds look like the salukis of today.

A bit later, near 3600 BC, a Sumerian tomb discovered at the site of ancient Eridu offers a more poignant reminder of the dog’s close relationship to man: Near the skeleton of a small boy, excavators found “a saluki-type dog.” Placed near the dog’s mouth was a bone, as if to give it sustenance in the afterlife.

Images of saluki-like hounds also appear on one or two Egyptian artifacts from the Pre-Dynastic period before 3000 BC, and a few images appear on objects from the Old Kingdom. During the New Kingdom, the saluki was widely used as a decorative motif.

The saluki came to the attention of the West somewhat later, although from the fifth century BC on, saluki-type hounds appear in hunting scenes on Greek vases. The Romans’ familiarity with these graceful hounds is evidenced in the many hunting scenes depicted on Roman mosaics in North Africa and Asia Minor.

In China, the story of the Emperor Kao Wei in the mid-sixth century of our era suggests that the saluki had become established in the Far East by then. Kao Wei owned a saluki he called Ch’ih Hu, “Red Tiger.” The dog was fed the choicest meat and rice and, in true saluki style, he rode on a mat placed before the Emperor’s saddle.

By the beginning of the Islamic period, the saluki could be found from China in the East to Morocco in the West, though, over time, regional differences appeared in the breed. The further north the saluki spread, the larger it became; the salukis of Arabia, however, remained light, fine-boned and perfectly formed to race across the deep Arabian sand.

According to most breed standards, the saluki can range from 58 to 71 centimeters (23–28") at the shoulder, and its coat may be feathered or smooth. (Feathering refers to the long silky hair that, in many cases, is found on the ears and tail and at the back of the saluki’s front and hind legs.) As feathering has little to do with hunting prowess, the Arab looks more for other qualities: a long muzzle, a deep chest, a tiny waist, and hocks well let down.

As early as the 12th century, Crusaders began to bring salukis back to Europe, where they were greatly admired. By the 16th century, the saluki had become especially popular in Italy, where in 1544 Duke Cosimo de Medici commissioned a bronze relief of his favorite saluki from the celebrated goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini.

The popularity of the breed was renewed in the 19th century, when such well-known British travelers as Lady Anne Blunt, Vita Sackville-West and Gertrude Bell each adopted salukis during her travels. In her book A Pilgrimage to Nejd, Blunt commented more than once on her hounds’ extraordinary speed and stamina.

Yet as every fancier knows, it is neither speed nor stamina alone that makes the saluki such a formidable hunter. Rather, it is the quick thinking required to actually catch the quarry. As coursing enthusiast John Burchard likes to say, “It’s not what the head looks like; it’s what’s inside the head that matters.”

Burchard’s enthusiasm for saluki coursing came from an interest he developed in falconry as a post-doctoral student. In Arabia, falcons are often paired with salukis, and it wasn’t long after Burchard took a consulting position with Aramco in Saudi Arabia in 1970 that he acquired Sha’ila, a lovely little saluki of Al Murrah tribal stock.

Sha’ila was fawn-colored, affectionate and extraordinarily swift. She accompanied Burchard during the two winter seasons he spent as a member of King Khalid’s hunting party, and she won much admiration from the king’s falconers, many of whom were Al Murrah tribesmen.

Most of her offspring inherited her winning ways, and a number of Sha’ila’s descendents became coursing champions. Two of them—Baomid and Behzad —won Swiss racing championships in 1986, and that year Baomid also won the Belgian championship.

Like Burchard, Sir Terence Clark has a soft spot in his heart for the Al Murrah saluki.

|

| Contemporary descendants from Al Murrah bloodlines include Najmah, above, and Sha'ila, below. |

|

Trained as an Arabist, Clark learned about the feats of the saluki long before 1985, when he was appointed British ambassador to Iraq. On that posting he acquired two Iraqi salukis named Tayra and Ziwa. When Ziwa died some years later, Clark and his wife, Liese, felt there was nothing to do but to find another saluki to replace her.

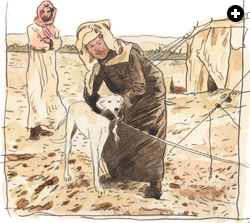

In the meantime, the Clarks had moved on to Oman, so it was from there that they undertook a driving trip through Saudi Arabia. En route they stopped in the Al Murrah village of Anbak. There they spotted “the little face” of a saluki peeking out from under a tent flap, and both say they knew in that moment they had discovered what they were looking for. An hour later, Clark parted with his brand new binoculars and put the saluki, named Najmah, on the car seat for the long drive back to Muscat.

|

A modern Al Murrah man holds a young saluki. |

Najmah later accompanied the Clarks back to London, where her pup Thalooth went on to become one of Britain’s top saluki coursing champions in recent times.

Clark counts himself lucky that he found Najmah when he did. Recently a friend of his traveled to Anbak hoping to acquire a saluki of her own, but she reported there were none to be found.

There are good reasons for this scarcity, of course. Neither the Al Murrah nor any Bedouin need salukis to provide food for them. Over-hunting in the 1950’s—by wealthy city dwellers with guns, not by Bedouins with salukis—depleted wildlife and ultimately led to widespread hunting bans.

Even so, Clark remains optimistic. He notes that a renewed interest in saluki heritage is leading some Arabs to establish kennels to breed fine salukis. And though the anecdotal evidence from Anbak suggests otherwise, Clark remains convinced that “typical” salukis can still be found in the small settlements where tribal people have always regarded them as an integral part of life.

Clark also sees renewed interest in these hounds in other parts of the saluki’s range, particularly in North Africa and Kazakhstan, thanks to an altered political climate.

The saluki also continues to do well in the West. Knapp died in 2000, but such fanciers as Marilyn LaBrache Brown of Washington and Sue Ann Pietros of Florida continue to breed from the Abdul Farouk I pedigree. In 1991, one of his descendents won for Pietros the Saluki National Specialty championship, and in 2005 the granddaughter of the 1991 winner won the same competition.

The Windswift breed too continues to prove successful, with at least one devoted fancier in the US. Since Elaine Yerty of Texas first acquired salukis from Vera Watkins more than 25 years ago, she has bred the “old-fashioned” desert-type dogs, whose looks have won them countless prizes in the show ring and whose natural instincts have also made them winners on the coursing field. And the Windswift dedication to retaining the qualities of the small, desert-bred saluki has always generated great interest on the part of Middle Eastern breeders. In her book, Saluki: Companion of Kings, Watkins tells of a contingent sent to England by “a Gulf shaykh” to find a suitable saluki. After visiting most of the kennels in the southern part of the country, they came at last to Windswift Kennels. There, to their great delight, they found not one but two salukis that they knew would meet the shaykh’s high expectations. As Watkins was careful to point out, these beautiful salukis were direct descendents of her great foundation dog—Sabbah the Windswift.

|

Jane Waldron Grutz, a former staff writer for Saudi Aramco, is now based in Houston and London, but she spends much of her time working on archeological digs in the Middle East. She wishes to express her gratitude to the many members of the Society for the Perpetuation of the Desert Bred Saluki whose insights enriched this article, particularly directors Sir Terence Clark, Elizabeth Dawsari, Herb Wells and Elaine Yerty. |

|

Norman MacDonald (www.macdonaldart.net) specializes in history and portraiture—of humans. This is his first set of animal portraits (not counting his own dog, Prince, his friend’s parrot or the occasional horse). |

This article appeared on pages 40-47 of the May/June 2008 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for May/June 2008 images.